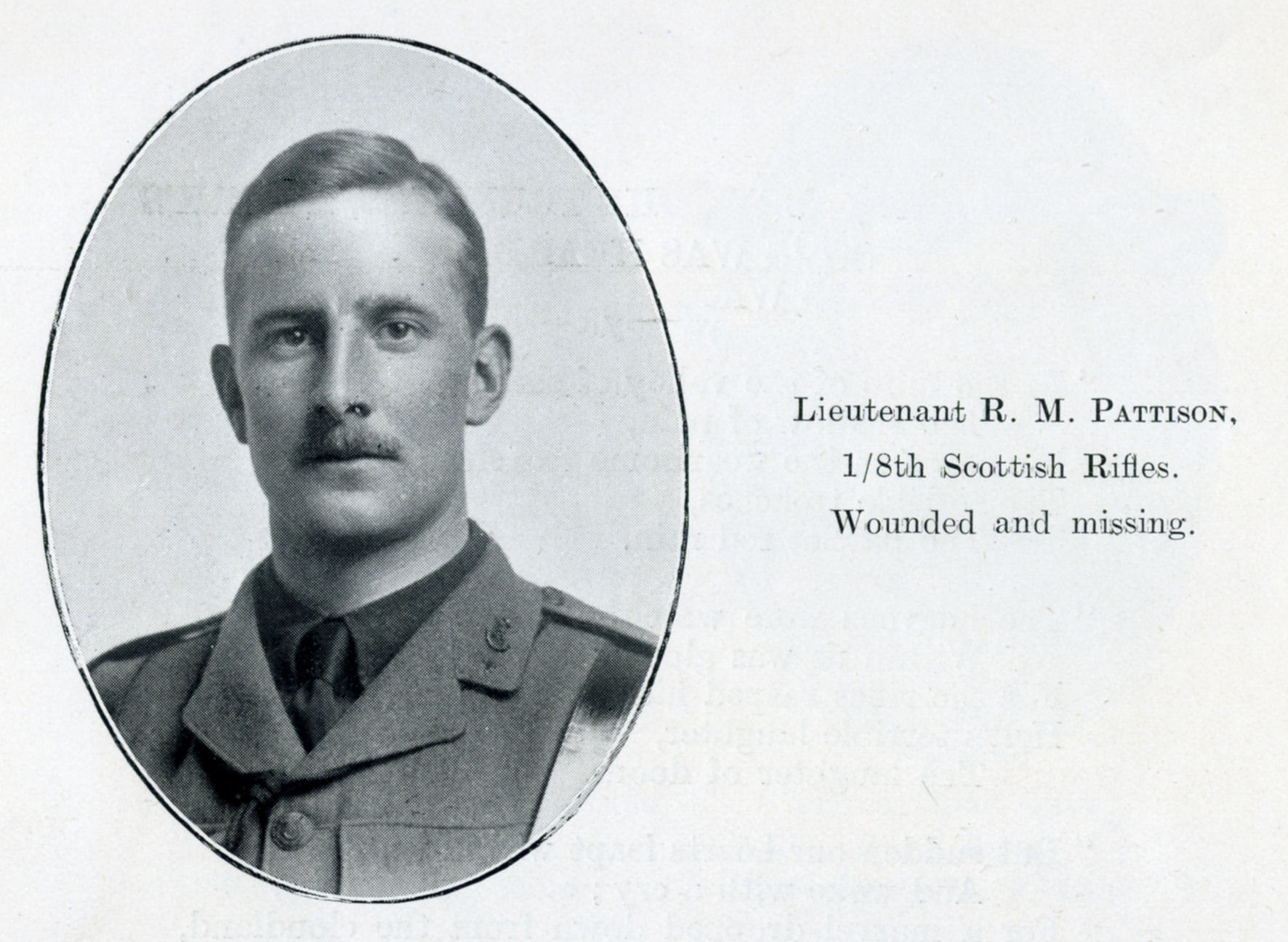

Son of James and Catharine Marshall Pattison, Drimnamona. Kilmacolm.

Robert M. Pattison, Lieutenant, 8th Scottish Rifles, 2nd Company "missing" since action at Dardanelles, 28th June, aged 25.

I do not think that many of us got much sleep - I know that to me the night was slow in passing - but dawn came at last, cool and beautiful, with a hint of the coming heat, and the dried-up sparse scrub had been freshened by the night's dewfall. One was impressed by the good heart of all ranks, but, whether it was premonition or merely the strain of newly acquired responsibility, I could not feel the buoyancy of anticipated success. I remember going round the line in the early morning and finding that there was some difficulty about the planks which the support and reserve companies had to put across the front trenches to facilitate passage, but these eventually arrived in time. The artillery bombardment which took place from 09.00 to 11.00 was, even to a mind then inexperienced in a real bombardment, quite too futile, but it drew down upon us, naturally, a retaliatory shelling. How slowly these minutes from 10.55 to 11.00 passed! Centuries of time seemed to go by. One became conscious of saying the silliest things, all the while painfully thinking, "It may be the last time I shall see these fellows alive!" Prompt at 11.00 the whistles blew."

Over the top went his men, to be met by a deadly stream of fire from all sides. Findlay soon realised that the attack was breaking down in No Man's Land. He sent back to brigade for reinforcements and moved forward up a sap with his Adjutant, Captain Charles Bramwell, and his Signal Officer, Lieutenant Tom Stout, to try and establish a forward headquarters. They did not get far; rank was no defence against bullets.

"Bramwell and I then pushed our way up the sap, which for a short distance concealed us, but got shallower as we went along, until first our heads, then our shoulders, and then the most of our bodies were exposed. We soon arrived at Pattison's bombing party, which I had sent up this sap. He had been killed, and those of his men that were left were lying flat; they could not get on as the sap rose a few yards in front of them to the ground-level, and the leading man was lying in only about 18 inches of cover. In any case they were still some 50 yards from the enemy trenches. Bullets were spattering all around us, and we seemed to bear charmed lives, until just as we arrived at the rear of this party Bramwell fell at my side, shot through the mouth. He said not a word, and I am glad to think that he was killed outright . I made up my mind that the only thing to be done was to collect what men there were and make a dash for it. I told this to Stout, and stooping down to pick up a rifle I was shot in the neck. At the moment I didn't feel much, but when I saw the blood spurt forward I supposed that it had got my jugular vein. I stuck a handkerchief round my neck and tried to get on, but I was bowled over by a hit in the shoulder. I tumbled back over some poor devil, and for a minute or two tried to collect myself. Up came young Stout and said, "I am going to try to carry you back, Sir!" but I wouldn't let him"

It was obvious to everyone around him that his wounds were serious, but Findlay was obsessed with the idea that he had to establish his forward headquarters and co-ordinate the next stage of the attack. In the end Lieutenant Tom Stout simply ignored him.

"I told Stout to send another runner for reinforcements. A few minutes later he came back and took me by the shoulders and some other good fellow lifted me by the feet, and together they got me back some 10 yards, and though a bullet got me in the flesh of the thigh, I was now comparatively sheltered while they were still exposed. It was then that a splinter of shell blew off Tommy Stout's head, and the other man was hit simultaneously. Gallant lads! God rest them!"

Findlay lay there, out of immediate danger but hardly safe.

"It was insufferably hot, and I recollect having a drink of water, and giving one to a boy called Reid, who lay mortally wounded alongside me. We all remained lying there in that sap, sometimes conscious, sometimes blessedly unconscious. The heat as we lay there was appalling, but things were gradually getting quieter; what we longed for was coolness. Reid, poor lad, was by this time in agony, he had been shot in the stomach, and all I could do for him was to give him a little more water. The day wore on into the interminable night, broken by he moans and agonizing cries of the wounded and dying, till dawn came coolly and quietly. In a moment of consciousness, I realized I was looking at a Turk who had appeared round a corner of the sap. We gazed at each other, and he went away. One of my own poor fellows was lying dead alongside of me. The Turk returned and again looked at me, and again disappeared. A second afterwards I saw a bomb hurtling through the air - it seemed to be coming straight for me, and with a great fear in my heart I managed to pull myself up, my knees to my chin, and my left arm cuddled round them. The bomb landed at my feet, and bursting, bespattered my left leg and arm and portions of my thighs. It seemed, however, to galvanize me into action, and another bomb coming over, I managed to roll over on to the other side of the dead lad and all its charge lodged in him. Somehow I then succeeded in getting to my feet and staggered back down the sap for a few yards over the shambles of dead bodies lying there, until I fell down. Another bomb came over, landing short, and I got up again and got farther back down the trench."

Findlay finally managed to stagger back to the lines. By then he was in a dreadful state: either very lucky or unlucky depending on one's viewpoint, having suffered some seven major wounds as well as a liberal sprinkling of minor scrapes from bomb fragments. His battalion had suffered over 400 casualties and 25 of the 26 officers had been hit. All in all the attack of 156th Brigade was a massacre with nothing achieved but a few insignificant gains on the left. Although more attempts to advance were ordered during the day they achieved nothing but further slaughter.

1. Second Lieutenant Robert Pattison. No Known grave.

2. Captain Charles Bramwell. No Known Grave.

3. Lieutenant Thomas Stout. No Known Grave.

SOURCES: J. M. Findlay, With the Eighth Scottish Rifles, 1914-1919 (London: Blackie & Son, 1926), pp.34-37