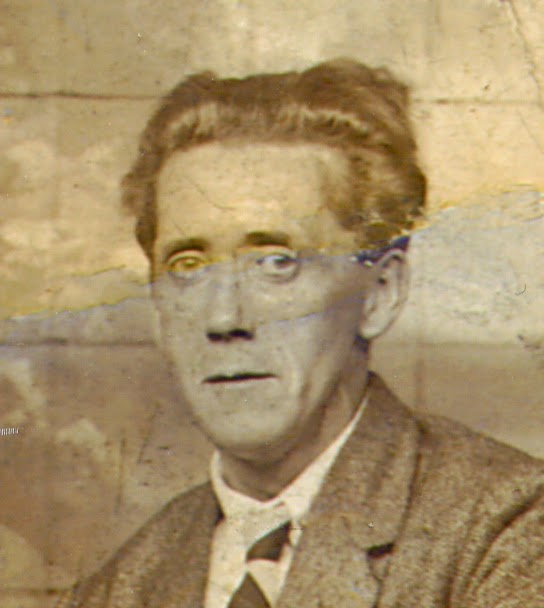

Sam Owen, of Greenock. Wearing his medals. He was captured early in the War.

Within the first six months of the First World War, more than 1.3 million prisoners were held in Europe. As the war progressed this number increased. Many local men were captured – often posted missing initially, it was a great relief to families when a letter came through to say they were now in German hands.

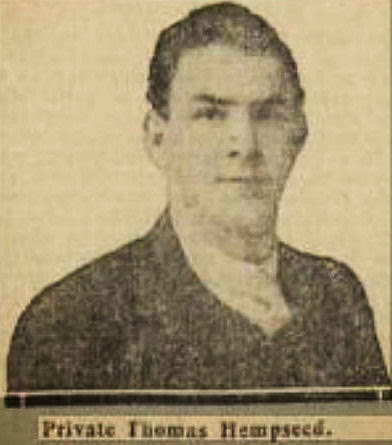

There are many remarkable stories. Two local men in particular wrote down their experiences- both captured in the early stages of the war. Thomas Hempseed, a local postman and footballer with Morton and Dunfermline, lost his leg but remained, at least in public, remarkably upbeat: “My football days are over; a centre half on crutches might serve as a novelty to a jaded public but he would be of little real value to his side as a player. Yet, although I am minus a leg – and my trusty right leg at that – I hope I am sportsman enough to accept my fate and to be happy in the knowledge that otherwise I am hale and hearty, as merry as a cricket, and as frisky, almost – I use the qualifying word knowing my limitations – as a young kitten”

Samuel Owen, of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers, had a far less positive outlook:

Danger, long travel, want and woe

Soon change the form that best we know;

For, deadly fear can time out do

And blanch at once the hair.

Hard times can roughen form and face

And what can quench the eye’s bright face;

More deeply than despair.

Sam was a POW for four years and stayed initially at one of the worst camps – Gastrow. He wrote his experiences down in a pamphlet “Four years in Germany as a Prisoner of War”.

The 30th October, 1914, will ever remain green in my memory, for it was on that date, after a long, stubborn resistance, the gallant 7th Division was cut up— but not defeated - by an overwhelming

German force. I, along with about 75 wounded and unwounded men of my own regiment and men of other units to the number of about 200, were taken prisoners by the Germans. This happened at Ypres.

Thomas’ experience was dramatic: It was on the fifth day of the battle that disaster overwhelmed me. We were at the Chateau when a party of the 2ndArgylls were mowed down by the enemy’s machine gun fire. I was hopelessly crippled, the right leg being riddled with bullets, and the left also having been hit. I lost consciousness for a brief space, and when I came to myself I found that I was surrounded by the dead bodies of my comrades of a few hours before. It was sometime ere I fully took in the situation, and then when I realised that I had been left behind mental anguish was added to physical uffering. For three days and nights I lay in that terrible field of the dead. Sometimes I think I might have gone mad but for the fact that, as the hours dragged slowly past, I became aware that there was yet another living soul in that field besides myself. In my agony of mind and body as I writhed on the ground there sounded in my ears the unmistakeable tones and broad accent of a fellow Scot.

Sweeter than any music did that sound on my ear. In a moment I had answered. In another, helpless as we were, we were trying to distinguish each other in the failing light and among the many who had

fought their last campaign. Wattie, is it you? I cried. Tom, came the response, it’s yersel. It was my comrade Private Walter Nelson, Wattie Nelson, of Dalry, a worthy gallant frae the Burns country,

wounded in the lungs, but ‘unco cheery’ for a that. I verily believe that but for this companionship neither Wattie nor myself would have emerged from that awful three days ordeal and retained our sanity.

We were divided by about fifty yards. Neither of us could move, neither of us had food or drink. But we did what we could to prevent each other giving way to despair, and were, on the whole, as cheerful

almost as Mark Tapley would have been under similar circumstances. However we were pretty well exhausted when at length succour reached us in the shape of two old French civilians who had been sent out to search the battlefield if perchance wounded might still be there. I remember seeing the grey beards and the kindly eyes of my rescuers – vague, spectral beings such as we meet with in a dream – and then I knew no more until I woke up in a hospital ward, where pretty French nurses, who, despite the German occupation, remained behind, flitting quietly about in their nun-like attire, and where on nice, clean, wholesome beds, like the one on which I reposed, were many in similar plight to myself. Now I am no friend of the Germans and I have suffered much discomfort and contumely at their hands, but this I will say, that the German surgeon who took me under his special charge at the Chateux hospital was as skilful as he was tender and kind.

At the start of the war, there weren’t enough places in Germany to hold all the POWs that were being taken. Camps were hastily constructed for them. Once these were built, prisoners were transported to them from the front. Prisoners were often given a hostile reception by civilians they encountered on these journeys, including Sam Own. “The train was going very slow, with frequent halts; we pulled up at another station and the doors were opened, and the men with the rocks (kilts) were ordered out; and not knowing what for, they tried to dodge behind the others, but the guards pulled them out: It was to let the people have a good look at “the ladies from Hell.” How they jeered, laughed and shouted vile insults at us, they seemed to have a very bitter hatred of Scotsmen. It was a good policy to hide your glengarry bonnet (If you had any). We stopped at a great many stations after that, and the same thing happened at each one.” When they arrived, the camps varied in their standards of accommodation and sanitation.

Gustrow in Mecklenburg was where Sam was sent. They were in a tent. “It was about 100 yards square, with walls 15 feet high and a high sloping roof; there were four entrances, and opposite each was a passage about 12 feet broad, and on either side a 2-feet high barrier; on the other side of the barrier a space of about 14 feet with a board dividing it lengthways in two parts, extending the whole length of the tent. The floor of these spaces were covered with a thin layer of straw for us to lie on. We lay in long rows side by side, each row head to head, for all the world like cattle; there were over 500 in the tent.”

Food was a source of misery for nearly all prisoners. They were provided with very little, and it was of poor quality. It was mainly a diet of soup and occasionally bread. The Red Cross and other charities added to prisoners’ supplies with packages of food, tobacco and other essentials and of course parcels from home. Sam recalled “it was very difficult to let our people at home understand what we wanted. If we asked for much, Jerry would not let our letters go through, and if we asked for a little our people thought we were well fed. All the British used to trek down every morning, hoping to see

their names. If their names were there they were paraded at 11 o’clock and had to state where they were expecting the parcels from; also show paybook, if any. If this satisfied them you were the right

man, your parcel was opened and examined; bread, biscuits and cakes were broken, tinned stuff opened or a bayonet stuck into it. It was heartbreaking to see them stick a bayonet into a tin of syrup, or

breaking cigarettes into small pieces; it would have been impossible to have sent out a machine gun wrapped in the “News of the World.” It made Jerry wild to see the prisoners getting such good parcels,

so he destroyed them as much as possible”

Health and hygiene were not usually given much priority at the prisons. As a result, POWs suffered from infectious diseases and body lice. Sam – “We had been about three months in the camp and never had a change of clothing. I had long since parted with my shirt: I was frightened it might have got the better of me. We were all in a terrible state with lice: we could take them off our blankets and clothing by the handful, and the straw we lay on was moving; we had to spend a couple of hours daily “lousing” oorselves to try and keep’ them down. If we had not done it they would have overpowered us”

Sam was sent to local farmers to work. They started making up small parties for farm work at the end of April, and I was included in a party of about 150 to go and work on the farms. We travelled about 50 miles on the train, and then at each station we were dropped off in small parties of no more than twenty. I was dropped off at a place called Bosestead; fifteen of us were then taken in waggons to Heidmullen in Holstein, a small village about six miles from the station. We were taken to the Boormeister’s house (the head man of the village.) The farmers got round about us then, and we were picked out and taken away by the people who had applied for us.

Allegations of cruelty, neglect and brutality were commonly made by prisoners of war. The POW experience varied – but mistreatment did occur. “....the French were no pals of ours, with few exceptions, they seemed to look down on us Tommies. If we asked a Frenchman for a fag end he would either not heed or put it under his foot. Almost every day we could see a fight between a Frenchman and an Englishman; and if the German guard caught them at it, the Tommy got a bashing, and perhaps tied up for a couple of hours, and the Froggy got off free. The first man I saw tied up was a Scotsman named Quiggly who hailed from Coatbridge. He had pinched the Frenchman’s bowl and they fought; and Quiggly had the Frenchie beat when the guard came on the scene. The French comrades started to explain in German to the sentries; and poor Quiggly got kicked and punched through the camp to the Commandant’s office. Whatever he was charged with, his trial was over in two minutes; he never had a chance to speak; he was ordered to be tied up for three hours, and he was taken to the posts and made to stand straight with his back against the post and his feet on two bricks. After he had been

tied tight to the post the bricks were taken away; that was another form of German culture.”

The war ended in November 1918, but POWs were not immediately released from captivity. Sam did not even find out that the war was over until December. “One sad incident happened as we got the order to leave. A man who had been a prisoner since 1914 dropped down dead almost at the gate. That cast a gloom over all. We were taken by rail to a seaport (I never found out the name), and then by steamer to Copenhagen, where we remained two nights before embarking for home. We arrived at Leith on January 2, 1919, after being prisoners for four years and two months.”

When Sam Owen returned to Greenock in 1919 he was a shadow of his former self. He became confined to a wheelchair and died in the 1930’s. He was born in 1885.

_143_124.jpg)

_104_205.jpg)

_143_167.jpg)

_143_188.jpg)

_143_173.jpg)

_143_186.jpg)

_143_149.jpg)

_143_142.jpg)

_143_156.jpg)

_143_117.jpg)

_143_109.jpg)

_143_131.jpg)

_101_205.jpg)

_143_190.jpg)

_106_205.jpg)

_117_205.jpg)

_93_205.jpg)

_42_205.jpg)

_143_135.jpg)

_143_138.jpg)